- Home

- Scarrows

- Mariners

- Cumberland

- Miscellaneous

Glasgow

A brief history of Glasgow, is followed by a section on some of the principle Glasgow Shipbuilders.

Glasgow, Scotland's largest city, has a history stretching back to earliest times. Stone Age canoes unearthed along the banks of the River Clyde suggest early fishing communities. Celtic druids were among the first identifiable religious tribes to inhabit the area. It's likely they would have traded with the Romans who, circa 80AD, had a trading post in Cathures, the earlier name for Glasgow. In 143AD the Romans erected the turf-built Antonine Wall stretching from the Clyde to the Forth to separate Caledonia to the north from Britannia to the south, but the wall was soon abandoned.

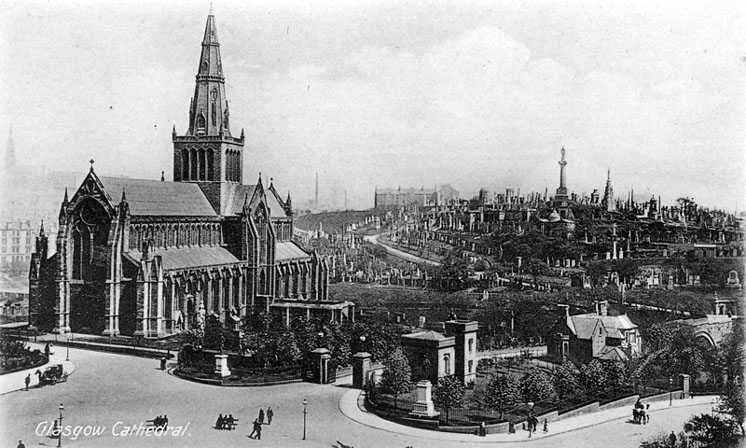

In 380AD St Ninian, the great Christian missionary, passed through Cathures, consecrating a burial ground, but beyond then little is known until the arrival of St Kentigern in the 6th century. St Kentigern settled in Glasgow (or Glas Cu, generally construed as "dear green place") in 543AD following exile from Culross where his miracle powers had aroused jealousy among his monastic brothers. In Glasgow, he established his Christian church on the banks of the Molendinar Burn, a tributary of the Clyde, where Glasgow Cathedral now stands. Such was his great popularity among his ecclesiastical community he was named Mungo meaning "dear one". Legend has it St Mungo performed four miracles in Glasgow, commemorated on the City of Glasgow's coat of arms, depicting a tree with a bird perched on its branches and a salmon and a bell on either side. When Mungo died on 13 January 603, he was buried in his own church, close to the spot where the only two known Glasgow martyrs of the Reformation were later burned at the stake. Between Mungo's death and Glasgow's establishment as an Episcopal see in 1145, little is known of the city's history.

By the later 12th century Glasgow's population had reached around 1,500, making it an important settlement. In 1175, Bishop Jocelyn secured a charter from King William making Glasgow a burgh of barony, opening up its doors to trade. In 1238 work began on Glasgow Cathedral, symbolising the city's growing role as a major ecclesiastical centre. In 1450 James II issued a chapter to the Bishop "erecting all his patrimony into a regality". Glasgow was now a Royal Burgh in all but name. Later that same year Glasgow Green became Glasgow's first public park. In the following year, 1451, the University of Glasgow was founded by Bishop Turnbull at its original site in the High Street, making it the second oldest university in Scotland and the fourth oldest in the UK. In 1471 Provand's Lordship (pictured), Glasgow's oldest house, was built, directly opposite the Cathedral building. Elevated to an archbishopric in 1492, Glasgow, by the end of the 15th century had become a powerful academic and ecclesiastical centre rivalled only by St Andrew's. Following the Reformation, James Beaton, Glasgow's last Roman Catholic archbishop, fled to Paris in 1560, taking many of the Cathedral's (pictured) records and treasured relics. Beaton's exile marked a significant move towards greater civic power and the emerging influence of the city's merchants and craftsmen.

In 1639 the National Covenant was confirmed by the General Assembly of the Kirk at Glasgow Cathedral. The Covenant had been signed in 1638 in Edinburgh, and was crucial in hastening the end of Charles I's authority, leading to his eventual execution some ten years later. Arguably the General Assembly's deliberations were the most significant in political terms of any meeting ever held in Glasgow.

Glasgow's foreign trade had also begun in earnest, traceable back to the 1530s, and it was undoubtedly booming by the time that Oliver Cromwell, hammer of the Stuarts, visited the city in 1650 just after he had invaded Scotland and defeated the Scots army at Dunbar. By 1649 Glasgow had become the country's fourth largest burgh, rising by 1670 to the position of second largest behind only Edinburgh. Glasgow's position was ideal for access to Edinburgh, the Highlands and Ireland, and her wealth continued to grow through a ready supply of natural resources, especially coal and fish.

The first cargo of tobacco arrived in Glasgow in 1674, and by the later 1690s the city had risen from its medieval slumber en route to its later accolade of "Emporium of the World". When Scotland eventually turned to the Atlantic, Glasgow, ideally placed on the west coast, came into its own. A dynamic business community seized its golden opportunity. Following the Treaty of Union in 1707, trade with the colonial New World burgeoned, and large quantities were being shipped in from the American tobacco states, especially Virginia. Glasgow's merchants in turn had contracts to supply Europe. By 1730 this trade with America was fully established, and Glasgow's tobacco lords had cornered the market, becoming in the process Glasgow's - and Scotland's - first millionaires. The American Revolution, however, delivered a vicious blow, and tobacco investors suffered. However, many shrewd Glaswegians had diversified into trade with the West Indies, importing sugar and making rum, and by the end of the 18th century Glasgow had become Britain's biggest importer of sugar.

In 1770, civil engineer John Golborne devised a way to flush the silt layers from the shallow Clyde riverbed by erecting a series of jetties along the banks, so that by 1772 large vessels were able to sail right up the river into the city for the first time, allowing for even greater industrial expansion. James Watt, one of the pioneers of the steam engine, helped supervise this operation encompassing 19 miles of the Clyde. This radical transformation of the river, assisted by the establishment of Port Glasgow near Greenock, was the catalyst for Glasgow's "golden age" of shipbuilding and heavy industry. As the Industrial Revolution took hold at the start of the 19th century, Glasgow's new industrialists were expanding their manufacturing bases, particularly in soap-making, distilling, glass-making, sugar and textiles. Textile production used coal in the steam-driven cotton mills and power-loom factories. Other industries included bleaching, dyeing and fabric printing.

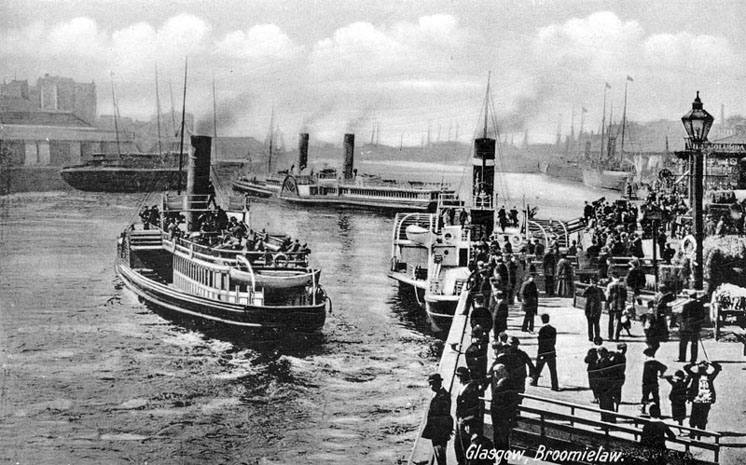

Glasgow Broomielaw

Glasgow's population was also increasing dramatically, as deposed immigrants from the Highlands in the 1820s and thousands fleeing from the potato famine in Ireland in the 1840s provided a vast pool of cheap, unskilled labour. With its growing industrial importance Glasgow also attracted large numbers of other immigrants, in particular Jewish, Italian and East European, who contributed greatly to the economy and local community. At its height, the cotton industry employed almost one third of Glasgow's huge workforce, but like the tobacco industry it was badly hit by external factors, especially the American Civil War of 1861, and, closer to home, increasingly tough competition from cities like Manchester.

Ever resourceful, Glasgow turned to a wide range of heavy industries, especially shipbuilding, locomotive construction, and engineering, which could thrive on the abundant supplies of iron ore and seams of Lanarkshire coal to fuel the ironworks. From 1870 until the start of the First World War Glasgow produced almost one fifth of the world's ships. These were heady days, in which Glasgow ranked as one of the finest and richest cities in Europe and acclaimed as a model of organised industrial society. Grand public buildings and a host of museums, galleries and libraries were built. Glasgow had more parks and open spaces than any other similar European city, along with a regulated telephone system, water and gas supplies. Little wonder that Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote in 1857: "I am inclined to think that Glasgow is the stateliest city I ever beheld." Glasgow's pride in these great achievements was openly displayed in two Great Exhibitions of 1888 and 1901, both held in Kelvingrove Park. Glasgow was now unquestionably the "Second City of the Empire".

The story of 20th century Glasgow after the First World War, is in bleak contrast to the previous century, marred by industrial decline of enormous proportions. Major economic downturn resulted in Glasgow being classed as a "depressed area" in the 1930s, although this era did coincide with the proud launching from John Brown's yard in Clydebank of the two great Cunard liners, the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth. "Clyde-built" remained synonymous with quality. The hosting of the illustrious empire exhibition of 1938 in Bellahouston Park was another significant event. The downturn in shipbuilding was matched by the decline in locomotive manufacturing. Glasgow had built one quarter of all locomotives in use anywhere in the world. Many were exported by ship, and a massive crane able to hoist an impressive 175 tons had been erected in 1931 on Stobcross Quay to load these engines onto ships. This Finnieston Crane remains one of Glasgow's best-known landmarks.

Immediately after the Second World War, the need for the country to replace lost shipping vessels slowed the industrial slump, but, come the 1950s, the demand for merchant and navy ships had dwindled drastically. The heavy industries could no longer compete with much cheaper labour costs of emerging competitors overseas. One final statement of shipbuilding glory came in 1967 with the launching of the Queen Elizabeth 2, but this was the finale of the great industrial days. The time for radical change was due, and in a remarkably short space of time a whole new economic base was created, centred on the service sector.

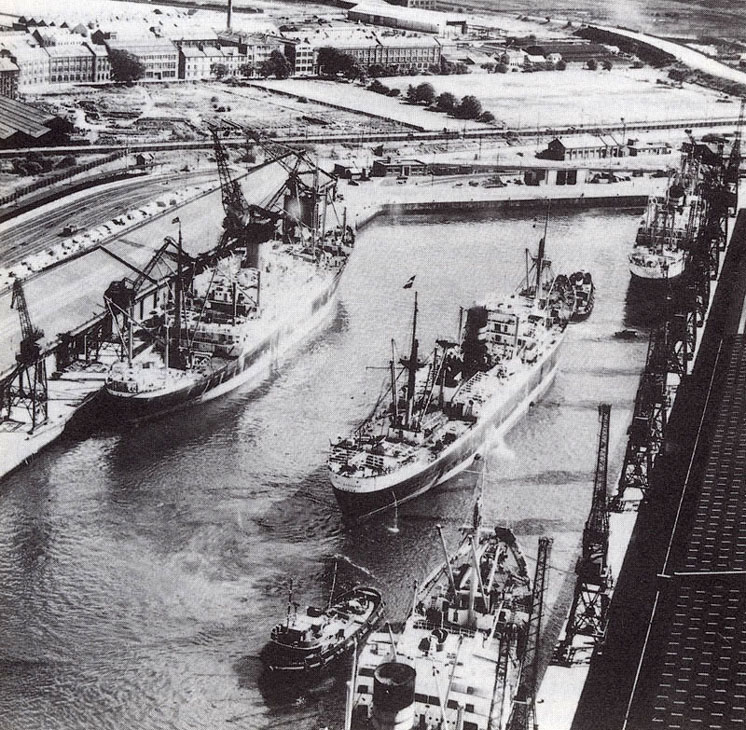

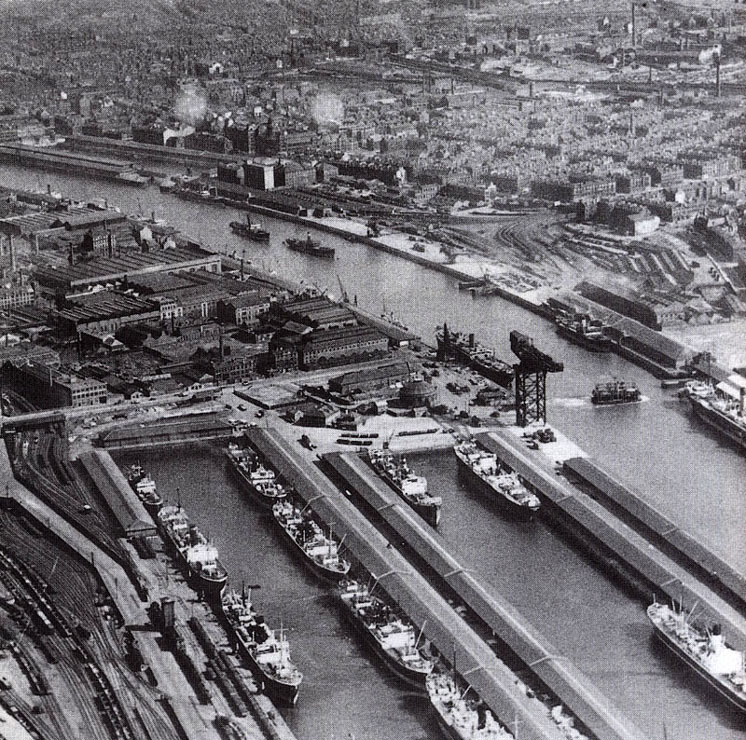

Glasgow Queens Dock

Imports

| Goods | Place of Origin |

|---|---|

| Tobacco | Virginia |

| Sugar | West Indies |

Exports

| Goods | Destination |

|---|---|

| Locomotives | Britain |

| Coal | British Empire |

| Herring | British Empire |

| Textiles | British Empire |

| Plaid | British Empire |

Industry

| Port Industries | Other Industries |

|---|---|

| Shipbuilding | Soap Making |

| Locomotive Construction | Distilling |

| Engineering | Sugar Refining |

| Glass Making | |

| Power Loom Factories | |

| Cotton Mills |

Scarrow Associations

| Scarrow | Period |

|---|---|

| John Scarrow II | 1828 |

| Joseph Scarrow | 1840 |

| William Scarrow | 1855 |

| Robert Scarrow | 1924-30, 1933, 1939 |

Ship Building

Before 1850, shipyards were distributed throughout the British Isles. These yards required merely suitable water, some experienced labour, and ample storage for timber. Early Scottish yards used local Oak or English Oak. The opening of the Forth and Clyde Canal enabled timber to be imported from the Baltic, and also Canada (primarily Quebec, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia).

The depletion of European timber supplies and an increase in ship size obligated the change from timber to iron. The first iron ship was built by Thomas Wilson in Glasgow in 1819. The early 19th Century saw the first practical marine steam engines produced - used in paddle steamers. In 1836 Francis Petit Smith patented an elementary screw propeller and from 1840 there was a steady production of screw ships. From the 1850s, the most popular steam engine was the diagonal, and this was to become the de-facto standard. Steel superceded iron in the 1880s, and the scene was then set for Glasgow to become the world's leading ship-building region.

From here, we will concentrate on the five shipyards that were regularly contracted by the Harrison Line of Liverpool - Charles Connell, W. Hamilton, Henderson, Lithgows, Alexander Stephen and Sons, and also one other, Denny Brothers.

Glasgow, George V Dock

Charles Connell of Scotstoun 1861-1968

Charles Connell and Co was founded in 1861, and continued under family management until 1968 when it became the the Scotstoun division of Upper Clyde Shipbuilders (UCS). Connells built a total of 510 ships in that period, although the yard was idle between 1931 and 1937.

The founder, Charles Connell was from Ayrshire, and served as an apprentice shipwright with Robert Steele and Co. Connells built sailing ships for the China trade, and had regular customers such as Harrisons, Brocklebank and Wilhelm Wilhelmson.

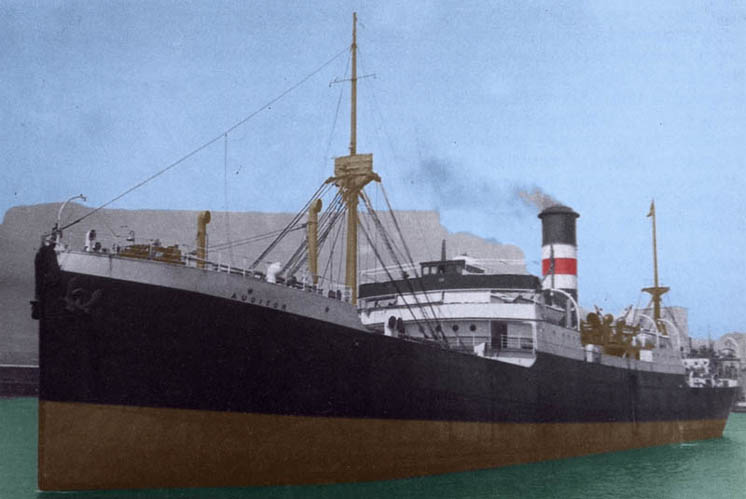

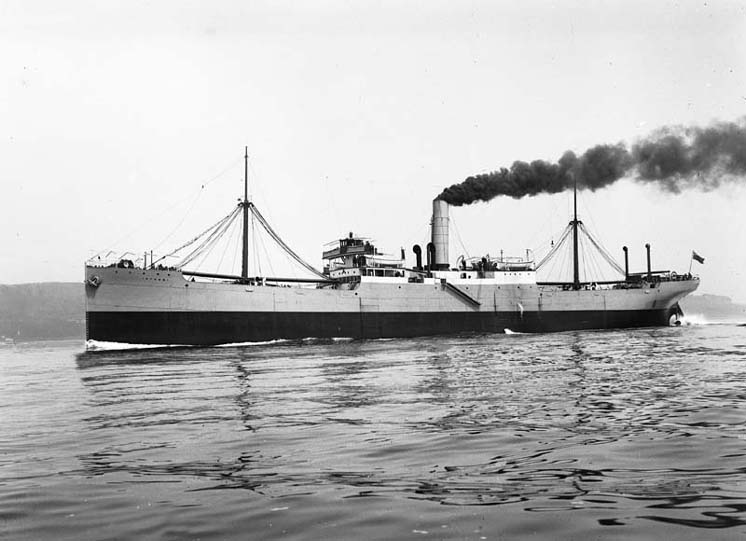

Auditor, built by Charles Connell and Co for Harrisons in 1924

William Denny and Brothers of Dumbarton, 1849-1963

William Denny and Brothers was formed in 1849 from Denny Brothers. Peter Denny set up an engine works in Dumbarton with John Tullock. In 1918 the engine works was merged with the shipyard. The shipyard exclusively used iron and was the first to change to mild steel in 1879. By this time they had regular clients such as the British India Company, P&O and the Union Steam Ship Company. The Royal Navy ordered from the shipyard between 1907 and 1959. Throughout their existence, Denny produced unusual vessels such as battery powered ships and hovercraft. After building 1,460 ships, the firm went into voluntary liquidation in 1963.

Denny's encouraged training and technical development, and in the late 19th Century produced a code of conduct to ensure smooth running of the firm. Included were such items as welfare schemes, confidentiality clauses, suggestion schemes, and meticulous record keeping. They established close relationships with Glasgow University, Royal Technical College and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The company supported worthy causes in Dumbarton, as its largest employer.

Colaba, built by W. Denny and Co Ltd for British India Company in 1906

William Hamilton of Port Glasgow, 1871-1963

William Hamilton founded a shipyard in 1871. In 1891 he took over John Reid's Glen Yard. The yard concentrated on trading ships, and produced two famous 4-masted barques in 1904 named Hans and Kurt. William Hamilton retired in 1919, and Lithgows took over his shareholding. The firm has a close association with the Brocklebank Line whose owners, Thomas and John Brocklebank, had a 50% shareholding in the yard. The yard was closed in 1963 and merged into the Lithgow East yard. The yard produced a total of 520 ships.

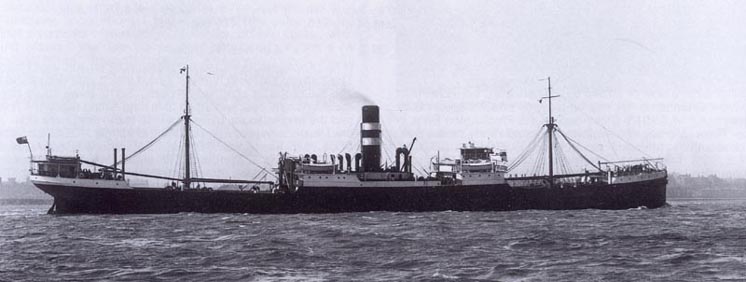

Intombi, built by Hamilton for Harrisons in 1912

D and W Henderson of Meadowside Glasgow, 1873-1962

David and William Henderson and the Anchor Line purchased the Meadowside shipyard from Todd and MacGregor in 1873 for £200,000. D&W Henderson constructed a wide range of vessels from simple barges to high class passenger liners. Hendersons also produced several large sailing ships and racing yachts including the Americas Cup contender Thistle. During the First World War standard merchant vessels were built, including Actor below. After the war, trade diminished and orders that were obtained were less lucrative. In 1935, Anchor Line collapsed, and D&W Henderson ceased trading. The total output of shipping stood at 470. The shipbuilding assets were sold to National Shipbuilders Security Ltd, and the ship-repairing facility and goodwill was sold to Harland and Wolff. The company closed in 1962.

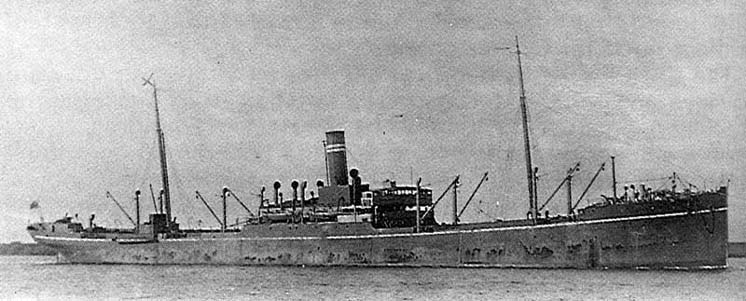

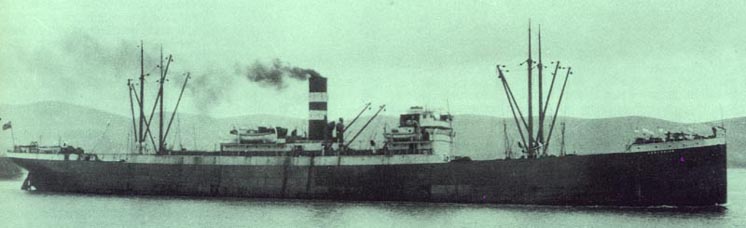

Actor, built by Henderson for Harrisons in 1917

Lithgows of Port Glasgow, 1918-1969

Lithgow's history began in 1874 when Joseph Russell and Anderson Roger formed Russell and Company and bought out the Bay Shipyard. In 1882 they took over Murray's Kingston Yard whose staff included William Todd Lithgow, their chief draughtsman. Lithgow was invited to become a partner. Russell retired in 1891, and in 1918, Lithgow's sons (James and Henry) renamed the company Lithgows Limited. Under their stewardship the firm produced a greater tonnage of shipping during the first half of the 20th century than any other UK shipbuilder. During the two wars Henry Lithgow ran the yards whilst James served as Director/Controller of Merchant Shipping.

In the interwar period, Lithgows bought controlling shares in suppliers, and also bought out the Fairfield shipyard. In 1969, the firm merged with Scott to form Scott-Lithgow.

Scientist, built by Lithgows for Harrisons in 1938

Alexander Stephen and Sons of Linthouse Glasgow, 1870-1968

The company originated in around 1750 in Burghead. It later moved to Aberdeen (1793-1829), Arbroath (1830-1843) and Dundee (1844-1893). A second yard was set up in Kelvinhaugh, Glasgow in 1851. In 1870 the company relocated the Glasgow yard to Linthouse. The Dundee yard was closed in 1893.

The firm built custom requested vessels of high quality, and were responsible for the first turbine powered vessel to cross the Atlantic (1905). Their customers included DFDS, White Cross Line, Imperial Direct West Indian Line and P&O. The Royal Navy also had many ships built at the yard including the aircraft carrier Ocean and very fast minelayers. The output of the Linthouse yard totalled 547 vessels. In 1968 the company was merged with Yarrow, Connell, Fairfields and John Brown to form Upper Clyde Shipyards.

Centurian, built by Stephen and Sons for Harrisons in 1906